Did you know the contents of a matrix can effect how fast a GPU multiplies it?

At first glance, that seems pretty unintuitive. Regardless of what’s in a pair of matrices, a GPU will have to do the same number of operations when multiplying them together. At least, that’s what the software level tells us.

The story gets more interesting at the hardware level!

When a matrix is sparse (more zeroes!), a GPU needs less transistor flips to do multiplications/additions with it (think an accumulator being able to stay at zero). This results in less power draw, causing less power-limit based throttling of clock speed, which in turn increases performance. Thus, more sparse matrices can have faster matmuls than their normal counterparts. When you break it down, it’s a pretty intuitive causal sequence!

But, it also begs some other salient questions. If matmuls between sparse matrices tend to take less power, do particular orderings of matmuls lead to better performance (think load balancing)? At what frequency do GPU’s regulate clock speed? How does one benchmark the FLOPs for a matmul in the first place?

Well, let’s find out!

All the code accompanying this article can be found here. Also, I highly recommend reading Horace’s original article before this one to get some context (it’s really good!).

To begin, let’s start with basic benchmarking. How can we determine the FLOPs performance for some GPU?

A multiplication between matrices of size (n x p) and (p x m) takes nm(2p - 1) operations. For the sake of simplicity, this article will focus solely on squares matrices of size n (which therefore take 2n3 - n2 operations). Note that this article will also benchmark using torch.matmul() which does not use optimizations like Strassen’s algorithm to reduce computational complexity.

After counting the number of operations in a matmul, all we need to do is time how long they take! The FLOPs will then follow as number of operations / total time.

While implementing this, there were a few small learnings I thought I’d share:

- GPU’s tend to have a warmup time when going from idle to active. This can impact performance for the first few operations but may be mitigated by doing some off-the-clock warmup operations beforehand or benchmarking over many matmuls such that the warmup is negligible.

- Nvidia GPU’s do have matmul speedups for sparse matrices, but they are for >= Ampere arch hardware. The experiments in this article were done on the Turing arch T4 GPU’s which come free with Google Colab, so we don’t need to consider that.

- Profiling power draw and SM (Streaming Multiprocessor) clock frequency can add overhead to the actual computations being done. Also, it can be somewhat inaccurate when done in Python code (it’s better to have a separate thread/terminal running whatever nvml query).

But, enough housekeeping. Here are some results I got from replicating the original article. When doing matmuls between two sparse matrices (torch.zeros) vs. two full matrices (torch.randn), I got 5.156 TFLOPs and 3.796 TFLOPs respectively. That follows what we would expect, but here are some takeaways from the results:

- GPU throttling is relative. The GPU throttled for both matmuls (my nvml query had a 0x00..004 error code indicating power-based throttling). However, the “SW Power Scaling algorithm” as described here lowered the voltage less for the sparse matrices (likely because of less drastic power spiking). This means that even if we aren’t able to stay under the throttling power threshold for a GPU, we can still eek out performance improvements by decreasing its relative power use over some operations.

- Sparse x sparse matmuls are faster than sparse x full matmuls which are faster than full x full matmuls. This follows pretty logically as the relative number of transistor flips for each is pretty easily intuited from their structure.

- I got less than the optimal number of FLOPs for a T4 GPU. Note that for mixed precision operations I should expect 8.1 TFLOPs. This could be attributed to a couple things, one of which is the throttling discussed earlier. There may also be an optimal sized matrix which doesn’t throttle and fully utilizes the GPU’s resources. To that end, memory limitations may have played a part as I was unable to load in matrices sized at the next power of 2 (32768). Fitting in the max size matrix would max out the parallelization the GPU gets to do and could increase TFLOPs. Wear and tear/physical conditions of the GPU could be another reason.

Now that we’ve recreated some of the basic profiling from the source article, let’s do some experimenting!

The biggest open question I have right now is whether or not particular orders of sparse/full matmuls can lead to better performance. We know that more transistor flips leads to more power draw, and therefore more severe throttling on average, but how can we mitigate this?

Well, how about load balancing? Let’s say we have a set of 50 unordered matmuls and know that roughly 10% of them are sparse. What if we uniformly distribute those sparse matrices throughout our calculations? After all, if sparse matmuls result in less power draw, then distributing them throughout a corpus of matmuls could create a distribution of power draw that is skewed lower (meaning the average amount of time spent above the power limit threshold would be lower –> less throttling).

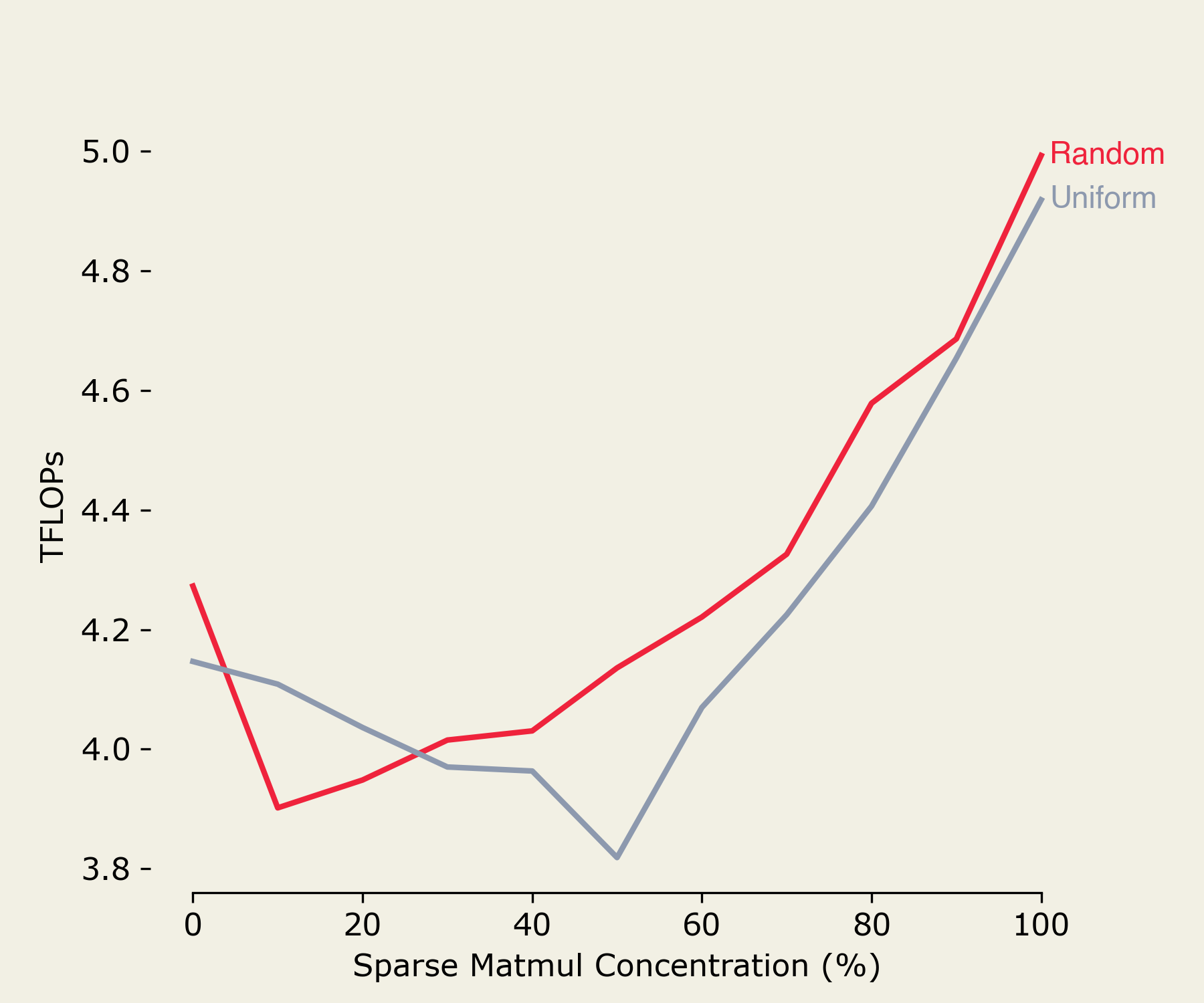

Well, let’s take a look. Here we compare uniform and random distributions for sparse matmul concentrations ranging from 0-100% of a total set of multiplications.

Interesting. The random distribution seems to work better… why is that?

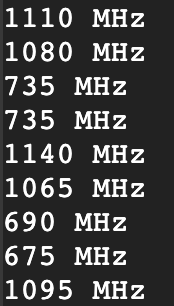

Well, to put it simply, the GPU regulates clock speed at a higher frequency than we do matrix multiplications. As such, the SW Power Scaling algorithm mentioned earlier can easily move the GPU’s clock speed up and down to accommodate whatever level of throttling is currently necessary to keep power under the max threshold. This is evidenced by running an nvml query for the SM clock frequency during uniformly distributed sparse matmuls:

As you can see, the frequency constantly changes and never really “load balances” as it hits the highs and lows each time.

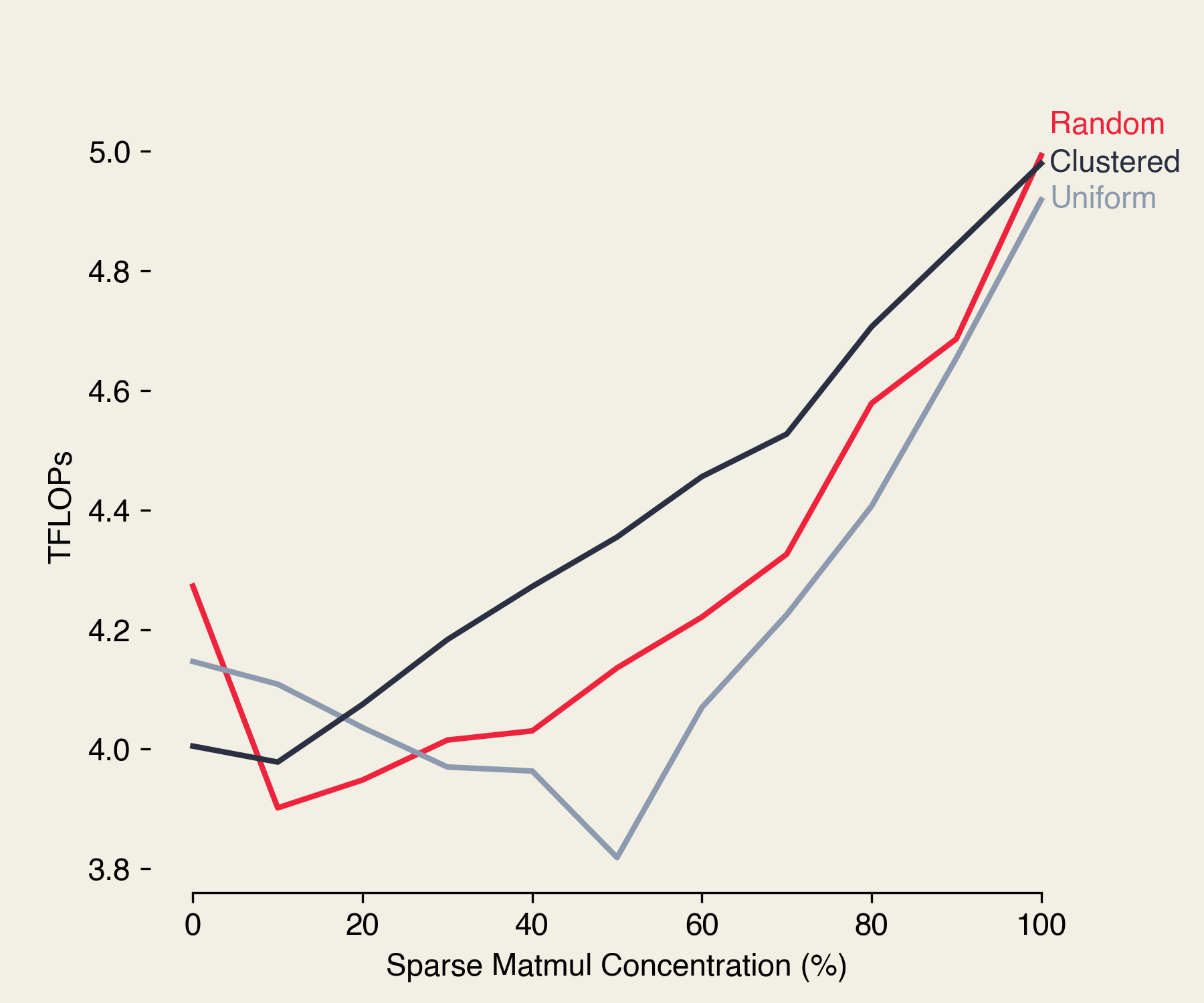

But this doesn’t really answer why the uniform distribution is worse than random. Is there a downside to having this constant switching of clock speed? To find out, let’s profile the TFLOPs when we cluster all the sparse matmuls in a corpus together. This way, those low and high power calculations are kept separate and the clock speed remains relatively stable between clusters.

Interesting! The clustered approach works pretty well. Why is this?

Well, two things come to mind.

First, more changes in throttling from the SW Power Scaling algorithm means the clock speed varies more often. Whenever the GPU changes its clock speed, the Voltage Regulator Module (VRM) does work shifting the power input of the GPU up and down appropriately–ergo, more overhead. It then follows that grouping matrices with similar power usage together avoids this flip-flopping.

Second, switching between sparse and full operations super often encourages more transistor flips as each type of matmul may tend towards certain transistor values (ex: sparse matmuls encourage more zeroes). By grouping similar scales of operations together, we reduce the entropy surrounding transistor state.

Pretty cool stuff!